This week’s study is all a bit meta, it loops back on itself and onto other aspects of my life and prior readings.

Trying to map it out on a virtual whiteboard gets confusing as the connections made are mulitdimensional. This study of the act of reflection in education is documented here in this Critical Reflective Journal which is in itself a recommended tool that can be used as part of reflection within an educational context.

Another layer of contortion comes as I consider the benefits and techniques of reflection in order to become a better teacher, at the same time as considering it as a teaching tool for my (future) students. There is a lot to unpack!

Reflecting on life experience is not something entirely new to me. I have done it in the corporate world and find it useful in my personal life. I will make time to assess how something went and figuring out how, if it happens again, I might have improved the situation by behaving differently.

What I have learned this week is that there are many formal models and frameworks around the act of reflection that can help me as an educator, but also help students as a key part of their learning. It forms a key part of both teaching and learning practice.

Prior to this week I had seen ‘reflecting’ as just something you did, and that you did it alone.

I was initially dismissive of the prospect of “methods for reflection”, that it was something that needed to be studied and formalised! But, like a number of my fellow students, I found that once I started reading into them found that they suggested processes or ‘lenses’ through which I might reflect that I had not previously considered.

There is something to be taken from these methods that can refine and improve my own process of reflection, and clearly there is a benefit to having frameworks that students, most of whom will have far less life experience, can turn to as they begin to actively reflect possibly for the first time in their lives.

David Kolb (1976) appears to nail the process, at least as I previously saw it, in his four-part cycle of: do it; think about it; formulate a theory about it; and do it again and see if it’s any better. More recent theories build upon those that have come before them.

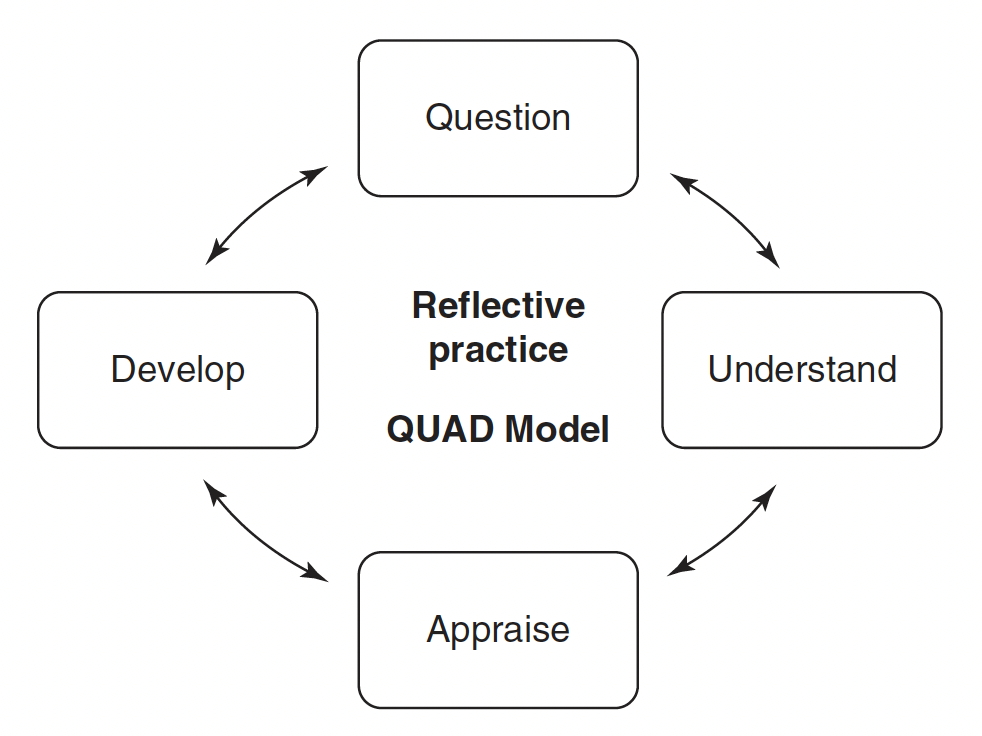

In his book, ‘Continuing Professional Development in the Lifelong Learning Sector’ Peter Scales et al paraphrase Kolb’s concept with their QUAD model…

..but they then go a little deeper by describing what in particular should be questioned, understood, appraised, or developed.

It is these pointers that, for me, take a seemingly obvious process – thanks Kolb – and add some useful considered guidance. This guidance encourages thought to spread further than maybe it would with no framework, yet constrains it enough to ensure that the process of reflection is not entirely open-ended.

A second interesting consideration this week, derived mainly from Scales et al, was the concept of collaborative reflection. That, amongst a team of like minded peers, it was permissible and highly valuable, to make explicit time for it and to reflect thoughts and opinions off one another.

“Lave and Wenger (1991: 37) believe that professional development is about ‘working

both independently and collaboratively to construct knowledge through inquiry-based

learning’.”

(Scales and Pickering, 2011)

Any reflection I’ve carried out myself has been deeply personal: mulling over a day’s work on the tube on the way home, or free-writing first thing in the morning to capture the myriad of thoughts and worries rattling around my head. These moments of highly valuable reflection have always been stolen moments; ones that I have carved out for myself. That an organisation might make time for explicit reflection and view the allocation of time to its pursuit is an interesting idea, and that one might collaborate in joint reflection is also quite an inspiring thought.

I have worked for corporations before that talk about post-mortems on projects, and sales opportunities but they never actually happened. It’ll be interesting to see how much of the theoretical best-practice that I am reading actually gets applied in education in the real world.

I was surprised, and somewhat inspired, this week to hear about people using what Donald Schon refers to as In-Action reflection. (Schon 1983, 1987)

This begins during your practice, in, for example, a teaching session. When something isn’t working, one draws on past experience to reason why and to adjust the teaching and learning

Schon (1987)

Until this moment I had only been thinking of reflection as as a posthumous activity, Reflection On Action, as Schon would put it. ‘In-Action’ reflection, an ability to see things aren’t working and switch to a new teacher method, is clearly something that requires sufficient experience in order to do it well; to understand what other teaching methods might be used or to adapt the environment better. Without that experience behind me I should make time, ahead of a lesson, to consider what other options I might use if my main plan doesn’t work, rather than just pushing through and hoping that through reflection I’ll do something better next time or the next cohort of students.

There are many other aspects of reflection that I have found interesting this week but the last one worth mentioning here connects reflection, as discussed in the recommended texts, with the reinforcement of learning at a neurological level.

Race’s ‘ripples on a pond’ theory contains within it a phase referred to as “Digesting”. This, according to Scales et al, is about “making sense of what we are learning. If we take a constructivist view of learning this process is one of personal meaning-making. We can’t just be given meanings by somebody else, we have to relate them to what we already know and our previous learning.”

This mental act relating learning to what we already know, to actively consider meaning and interpretation. Along with the act of journalling that recalls and contextualises new topics, these are forms of ‘retrieval practice’ which “strengthens the connections between neurone in long-term memory” (Oakley, Rogowsky and Sejnowski, 2021) which is key to solidifying knowledge and moving it out of its temporary location in working memory.

The act of reflection then is a multi-faceted tool. As educators it allows us to grow and become better at what we do working alone and together to actively consider the past and how changes to what we do might improve our ability to educate in the future.

It is also a tool that we should be teaching our students so that they can grow themselves and see how they have grown and improved over time. In the background the overt act of reflection for promoting and noticing growth also serves to embed what we are teaching into our student’s long-term memory. Better equipping them to absorb and understand the next topics we teach them that build upon knowledge we have already shared.

Reference list

Escher (1951). House Of Stairs.

Moon, J. (2005). The Higher Education Academy Guide for Busy Academics No.4 Learning through reflection. In: The Higher Education Academy Guide for Busy Academics. The Higher Education Academy.

Oakley, B.A., Rogowsky, B. and Sejnowski, T.J. (2021). Uncommon sense teaching : practical insights in brain science to help students learn. New York: Tarcherperigee, An Imprint Of Penguin Random House Llc.

Scales, P. and Pickering, J. (2011). Continuing professional development in the lifelong learning sector. Maidenhead: Open University Press.