There was some interesting discussion on this week’s webinar as to how long a lecture video should be when used in the context of a flipped classroom. One of our tutors argued that research showed videos shouldn’t be longer than 10 minutes, but a fellow student an I both said we preferred to watch a single longer video and pause, make notes etc. than have to keep playing the next video. Cutting a video into smaller ‘bite-sized chunks’ seemed a little patronising to me. Like it was a check to make sure the student was still awake.

The book ‘Podcasting for Learning in Universities’ was cited by our tutor as being a place where this recommendation of length came from, but whilst it refers to the length of podcasts or video podcasts made for some of the case studies of being around the 10-minute mark it doesn’t explicitly, in the chapters I’ve read at least, cite why that is an ideal length.

‘Uncommon Sense Teaching’, a slightly more modern text than ‘Podcasting for Learning…’, is a bit more explicit on how long videos should be. Essentially advising that:

…the material is broken up into the smallest chunks possible. But not so small that a student needs to watch multiple videos in a row to understand a concept. Three to twelve minutes should be the amount of time required to give an explicit piece of instruction.

(Oakley, Rogowsky and Sejnowski, 2021, p.216)

A research paper by Dr. Larry Lagerstrom, of Stanford University entitled “The Myth of the Six Minute Rule: Student Engagement with Online Videos” is pretty dismissive of this generalised rule of thumb. It highlights that the ‘six-minute rule’ often applied to educational videos was simply born out of an analysis of 6.9 million MOOC video episodes which found the median engagement time of viewers of those videos to be six minutes, regardless of actual video length or content.

What Lagerstrom’s paper showed was that the six-minute rule didn’t really take into account student viewing behaviour in the context of educational viewing. That their viewing wasn’t linear and that whilst the median engagement time for a video in Lagerstrom’s study was 12-13 minutes the mean watching time was longer – students pause, rewind, and skip through parts of a lecture. Students also return to lectures multiple times with the report finding that, even for courses where the videos were 50-75 minutes long, 90% of students watched all of the videos. In fact, the distribution curve of how much of a video was watched showed they either watched all of it or none of it.

Most students had multiple watching sessions with each individual video, and when those multiple sessions are stitched together, a truer picture emerges. We found that for most videos, most students watched 90-100 percent of the video. In addition, we found that the students who did not fall in this category watched very little of the video, usually less than 10 percent. In other words, there is a bimodal distribution with most students either watching the video in its entirety (usually over multiple sessions) or not at all.

(Lagerstrom, 2015)

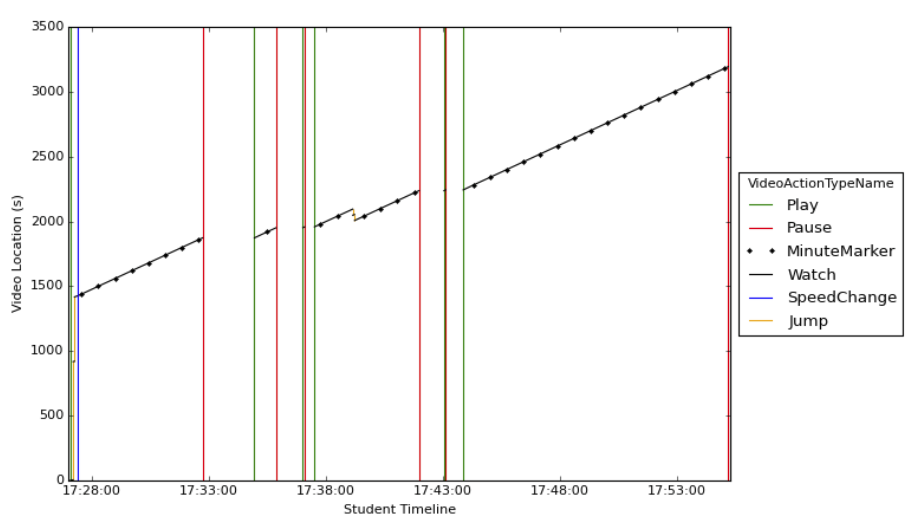

The analysis is interesting, with data showing where students pause, watch and jump material.

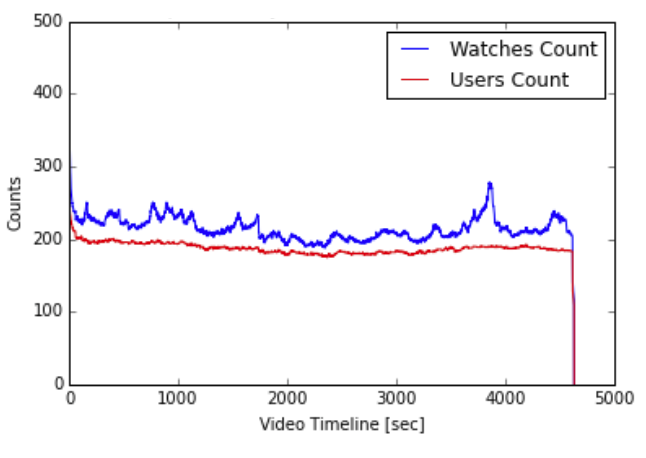

Or where users and watches for each minute of material can be compared to show which areas of a video was most difficult to comprehend and therefore watched more times over by the students.

The data from Lagerstrom’s 2015 report is backed up by a student’s anecdote that is relayed in ‘Podcasting for Learning in Universities:

I need one and a half hours to study a 15 minute lecture because I need to take notes from whatever he’s saying, so sometimes I need to pause. I need to take some time to write and some time to understand the thing because there’s no point in just writing down all the things – so I pause it sometimes or go back to the slide before.

(Gilly Salmon, 2009, p.84)

So it’s not that students won’t watch a lecture that is longer than say 6-10 minutes, they will watch much longer lectures, but we do need to be mindful of the length of time it will take the student to absorb the learning from that lecture. The time they spend absorbing the lecture is an order of magnitude longer than the actual video length. Not dissimilar, I guess, from the time we spend putting the videos together in the first place. We cannot assume if we’ve condensed learning into a short space the students won’t need long to comprehend and understand it.

If making longer lectures though we should be mindful that students don’t have an infinite attention span. Uncommon Sense teaching warns that

It is only when you have your students’ attention that other neural mechanisms can start locking in the information the student is trying to understand and absorb.

(Oakley, Rogowsky and Sejnowski, 2021, p.220)

Within our videos, we need to employ motion, sound, and anything unexpected to trigger bottom-up processes in the brain to keep the viewer alert. Once a scene stays the same for too long, cautions Oakly et al, a student’s attention will tend to wander. Changing camera angles, and using images, animations or audio effects are all devices that can and should be deployed to retain student attention and help embed quality learning whatever the length of the video.

Reference list

Gilly Salmon (2009). Podcasting for learning in universities. Maidenhead Open University Press, p.84.

Lagerstrom, L. (2015). The Myth of the Six Minute Rule: Student Engagement with Online Videos. In: 122nd ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. [online] 122nd ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. Available at: https://monolith.asee.org/public/conferences/56/papers/13527/download [Accessed 19 Jun. 2023].

Oakley, B.A., Rogowsky, B. and Sejnowski, T.J. (2021). Uncommon sense teaching : practical insights in brain science to help students learn. New York: Tarcherperigee, An Imprint Of Penguin Random House Llc,.

One thought on “720 – 3 – The Myth Of The Six Minute Video”

Comments are closed.